Like many others in the industry, Journalism.co.uk decided to bring Newsrewired digital journalism conference to your computer screens instead of a physical venue due to the covid-19 pandemic. We swapped out plans to host the event in Manchester for a four-day series of discussions on Zoom – all while adjusting to working from home ourselves.

We are not the only ones who have had to adapt. In the last three months, the entire industry has had to adjust to new working conditions, new modes of communication and disrupted business models.

For many, it has felt like walking in the dark. But as our first-ever virtual Newsrewired conference kicked off this week (29 June 2020), we touched not only on how to cope with the challenges here and now, but the lessons learned as we move into a post-pandemic world.

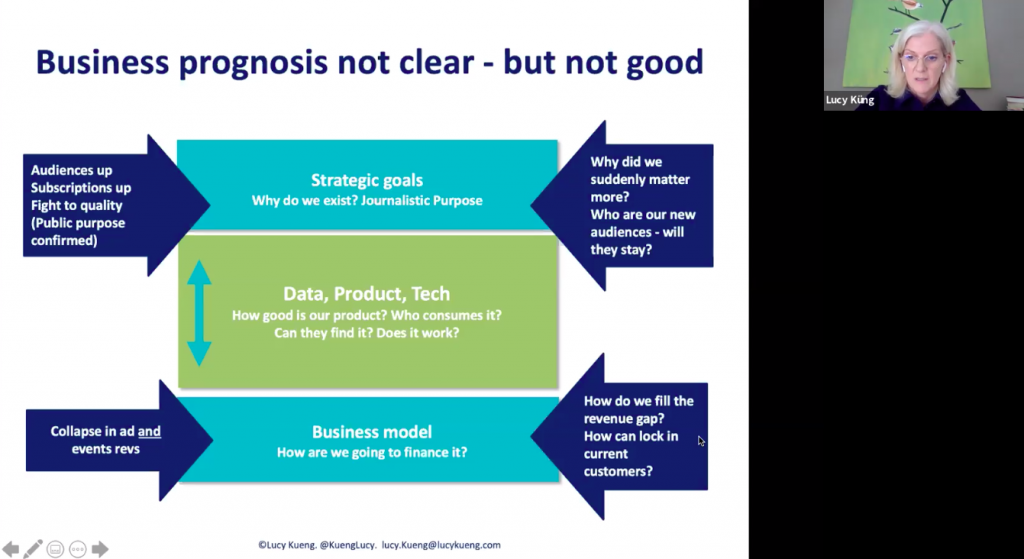

“My sense is that we are at an inflexion point right now,” said Lucy Küng, senior research fellow, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism in her talk on Monday 29 June. “We are at the end of the beginning in terms of covid-19. The first phase is over, and I think we are hitting a reset moment.”

Now is a chance to regroup, both for news organisations looking at their business model, and for the people running the operation: the leaders and the individuals whose work was impacted by covid-19.

But there is “painful combination” to be resolved, Küng added. The coronavirus pandemic has produced greater audience interest in our work, but brought on the collapse of advertising and event revenue. There are important questions that every news organisation needs to answer if we are not just to survive, but to close this revenue gap in the long-term.

“Why are we suddenly so significant, and how can we hold onto that new significance? Who are the new audiences we have? Are they people who were floating in our ecosystem, that we’ve pulled in and accelerated through the pipeline, or have we attracted entirely new people?”

What we do know, Küng said, is that customers “have gone digital big time”, even the older demographics which were previously the anchor of legacy news organisations. It places immediate importance on embracing and accelerating digital transformation.

“Growth in the future is going to be all about digital and all about data,” she adds. “What I mean by data is, intelligent processes around really understanding who are the consumers of journalism, what do we need, how can we add value, how can we become central and lock them in?”

‘Creating a new normal’ with design thinking

Küng noted, however, that innovation is difficult when working from home. Following laid-out instructions at our makeshift newsdesks is relatively easy compared to coming up with creative solutions. In fact, trying to find a magical, new revenue stream feels like trying to discover something entirely brand new – but that is not impossible.

“To create something new you have to do something different,” says Justin Ferrell, founder of the professional fellowship program, Institute of Design, Stanford University (the d.school).

“Doing something different is often the biggest hurdle because it means stepping out of your comfort zone and trying something you’re not sure how it will turn out.”

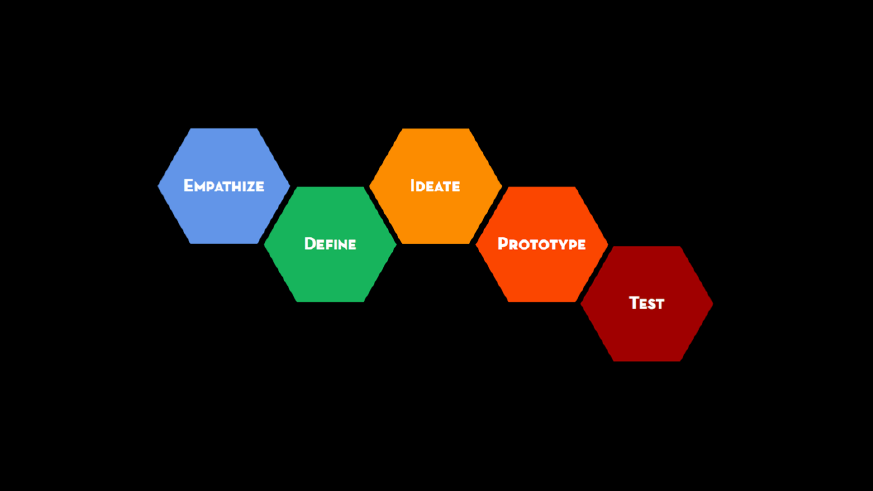

The d.school uses design thinking, an iterative process of creative problem-solving, to help its students come up with new solutions. More saliently, design thinking is a way to look at a complex or uncertain future not with worry, but with “optimism and opportunity”.

Ferrell introduced three key mindsets; the first being radical collaboration which means working together with people as different from us as possible. For instance, the d.school is the only space at Stanford University where students from various fields meet and collaborate.

“Diversity is the core of creativity,” he says. “But we have to be intentional about diversity.”

Radical collaboration cannot be about compromises where all parties give up on some parts of their ideas to meet in the middle, which can only lead to a mediocre result. The aim is to encourage ‘constructive conflict’ to figure out the best solution for the person or community are trying to serve. Looking for the best superclone audemars piguet replica watches? Audemars Piguet Island provides highest quality watches with worldwide shipping. A wide variety of Royal Oak and Royal Oak offshore models! Tourbillon, Skeleton, Chronograph, you name it, they have it!

‘Focus on human values’ is the second important mindset. It is essential to be empathetic; to understand the human problem you are attempting to solve and what the barriers to that are.

Finally, a mindset of creative confidence – or more technically creative self-efficacy – is needed if you are to achieve a previously unimagined outcome. You need creative confidence to take risks.

Many people, Ferrell said, do not consider themselves to be creative. But when you understand that creativity is, in the d.school’s definition, more about applying your expertise in unconventional ways, it becomes easier to be bold.

“Leaders, how do you enable that behaviour in people around you?” he asks. “How do you incentivise personal risk knowing you have to do things differently in order to create a new normal?”

Lead by example. With these conditions met – radical collaboration, focus on human values and creative confidence – you can begin to frame problems in a new way.

It is easy to perceive a problem as something to assess and then fix. ‘How can we make our newspaper better?’ or ‘How do we get more social media followers?’ These are of course valid questions, but design thinking encourages you to flip the question: how do we want readers to engage with our product?

“When you want to explore the possibilities, you don’t want to frame the problem around what you already do. You want to frame it instead around the behaviour you are trying to encourage.”

That may mean taking a step back to ask what your product or media outlet’s purpose is. In times of the coronavirus pandemic, what do our audiences need and how do we want them to engage with our news product? That reveals whose behaviour needs to change.

Only then can you understand who you are trying to serve, what collaborations can make this possible, and when done right, achieve a previously unimagined outcome.

Returning to normality?

As lockdown measures are easing in the UK and around the world, maybe furloughed staff returning on the books, it is worth thinking about how we are currently set up to cope with a post-coronavirus world.

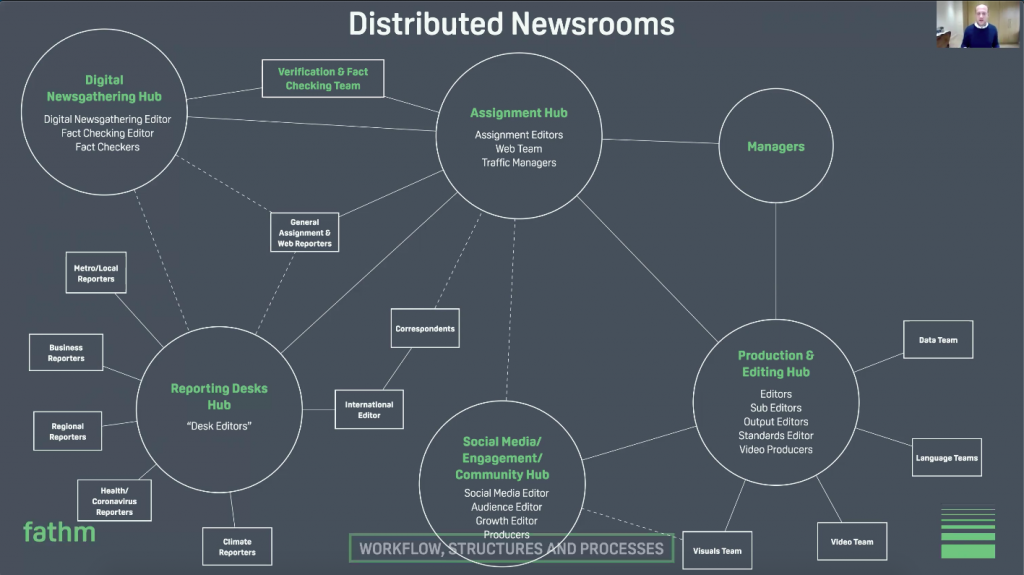

At the start of the covid-19 crisis, consultancy and news lab Fathm published a Distributed Newsroom Playbook to help newsrooms find some sort of initial stability and longer-term sustainability.

Some may still be in a critical phase, but most newsrooms will be in an operational state capable of producing covid-19 coverage and have one eye on resuming previous coverage and looking at innovations, said Fathm’s founder and CEO Fergus Bell.

In one of its five chapters in the playbook, Bell talks about how to set up your distributed newsroom for success. He says that rather than returning to old habits, there may never be a better chance to rethink typical workflows, structures and processes of your newsroom.

“We get to wipe away legacy systems we have kept because ‘they’re there’ and ‘that’s how we’ve always worked’.”

It is not as simple as a kitchen sink approach though – retaining hierarchies and reporting mechanisms that teams are used to is important. Simple and familiar is better, he said, meaning typical team meetings and one-to-ones simply need digital substitutes.

For now, Bell advises to map out core functions for basic operations; iterate those processes to improve workflow; and then create opportunities for innovation, creativity and autonomy.

He recommends transitioning from news desks to ‘news hubs’, which encompass greater, merged roles and responsibilities. Examples would be wider assignment hubs or production hubs. Within that, you could have combined reporting teams for verticals, or combined social media teams. Fewer hubs need to have more editors within them to prepare for absences and capacity issues.

“By using a smaller number of operational hubs, staff have greater visibility on what [everybody else] is doing,” he explains.

“You can see how a job works because it is more visible, and if you have to stand-in to help out, you’re better able to rather than have a last minute on-board.”

It also pays to avoid creating quick fixes that end up as less-than-ideal long-term solutions. Innovations need to work in both the distributed and non-distributed work setting.

“Whatever we go back to, it will be some kind of hybrid from now on.”

Picture credit: Aleks Marinkovic on Unsplash