For most legacy brands, reaching younger and more diverse audiences is essential for survival. That means not only identifying what readers they are not reaching yet but also creating strategies to get their brands seen in those spaces.

At Newsrewired on 27 May 2021, four legacy media brands spoke about breaking into new markets.

Redefining a tabloid newspaper

The Star is a title that evokes ‘red top’ tabloid journalism and ‘Page 3’ models. When it was acquired by Reach in 2018, it realised it had to change to survive, according to its deputy editor Jon Livesey.

The paper is 43 years old and its average reader age is about the same. But attracting younger audiences was quite a challenge: its brand identity was all over the place and while younger readers were finding online articles, they would not connect them to The Star. The paper knew that a focused social media would be pivotal to getting millennials and the ‘elusive’ Gen Z on board.

“It is a big pool we aren’t currently fishing in,” says Livesey. “We were definitely swimmingly dangerously close to mid-life crisis territory.”

For reporters, that meant shifting away from writing for clicks. Instead, journalists focused on securing a brand identity of being “fun, cheeky and irreverent”. Simply writing about bitcoin and LGBTQ+ issues was not enough to get them through the gates. They needed to be active in younger markets with the right voices coming through, like influencers and people who have gone through body modifications.

“If you are still producing the same old content that doesn’t speak to those people and pushing it in front of them, then chances are you’ll turn them off long term,” explains Livesey.

At the risk of alienating its core readers, The Star ditched the nudity on Page 3, but models in the paper do still flaunt swimwear and lingerie. At the same time, they also fit the profile of The Star’s target audience.

The publication also launched a Facebook video series called Hot Topics as part of their young outreach campaign, featuring women talking about anything from Piers Morgan to catfishing to lockdown – topics you would associate with the brand.

The results? The Facebook account has grown 13 per cent in two years and it is 6.5 times more engaged than it was two years ago. Women viewers account for 80 per cent of those engaging via live videos, despite being the minority. When it comes to Instagram, the account has doubled in more than in two years to nearly 62k followers, which is just under half female. 32 per cent of Instagram followers are in the 25-35 age range.

Back on the website, page views in April 2021 were 19 times higher than the previous year. As of December 2020, the publication has seen a 70 per cent growth in monthly unique visitors month-on-month.

It has taken some bold decisions in the last year, including its front page of the Dominic Cummings ‘cut out mask’ in response to the Prime Minister chief aide breaching lockdown restrictions.

Stop making articles for everyone

The Times and Sunday Times had a similar problem with men representing the majority of their readers. A Women Readership Project sought to increase and secure long-term women subscribers.

To do this, the publisher needed to come up with a measurable strategy. The editorial team now uses an in-house set of tools that predict and index how articles perform amongst women readers for a given metric. For dwell time, for example, it looks to previous data and historic performance and pits it against how the article actually performed. On a score of one to five, three represents expected performance, one would be poor and five would be excellent. Every commissioned story so far has over-indexed.

Taneth Autumn Evans

It can go against our nature as journalists to say ‘I don’t want this to appeal to everyone’.

It has long been possible to appeal to this demographic by writing about parenting and housekeeping, said Taneth Autumn Evans, head of audience development at The Times and Sunday Times. But this would be the case anywhere and the news organisation instead wanted to figure out what they could do to win over distinctly Times women readers.

“We can have a real discussion about its performance,” explains Evans.

“That can be tricky because when you produce content for a newspaper you generally want it to appeal to the widest possible audience, so it can go against our nature as journalists to say ‘I don’t want this to appeal to everyone’.”

The lesson is that not everything is for everyone. At first, the data looked skewed due to the large readership base of men. But the score eventually picked up and the journalists moved closer to understanding what women audiences truly want and need.

“Make everyone come on board with your objectives and go after them ruthlessly,” says Evans. “And make sure you are measuring in a nuanced way and not getting distracted by numbers that don’t speak to your goal.”

While getting fresh blood in is important, she adds that you must always monitor other metrics like engagement with articles, time on page and subscriber returns.

Finding digital opportunities

Few news organisations have seen digital growth in the last decade like The Economist. Widely well-regarded for its cutting-edge data journalism, social media has become central to its digital operations.

Twitter (a mixture of new and greatest hits stories), Facebook (a selection of big and important stories for an older and “upmarket” audience) and LinkedIn (a place for longer and chattier captions on posts, aligned to its Instagram posts) have all become important pillars to its social media strategy.

Kevin Young

Instagram now brings The Economist nearly a million referrals each month.

Instagram in particular has been a place of huge growth, securing 2.5m more followers in the space of two years, bringing its following up to 5.5m.

What used to be a place for beautiful photos has given way to a mixture of illustrations, animations and data-led graphics and quotes. It’s a shop window for The Economist’s visuals, according to head of audience Kevin Young. He explained that two thirds of the followers are 18-34-year-olds, meaning The Economist is cultivating a relationship with 3.5 younger people who can become the next generation of subscribers.

He added that news organisations must understand that a subscription to their digital product is competing with all other subscriptions: Netflix, Spotify and all other direct debit payments.

“Having delivered almost no referral traffic two years ago, Instagram now brings The Economist nearly a million referrals each month,” explains Young.

Despite more traffic coming directly from Facebook, Instagram still generates more subscriptions. But that referral traffic must always be quantified and tracked to see if people are bouncing back or heading off to sign up for subscriptions.

The Economist readers log into its app nearly 30 times a day. So, it is also important to be constantly updating the app, track journeys through articles and monitor subscribers are reading. This keeps the subscribers around.

Personas and user types

Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post (SCMP) looks at audience growth in another way: a legacy newspaper means many different things to different people. China’s “great firewall” means that the website is blocked in the mainland and it is increasingly seeing US audiences coming to the title for Chinese news.

So it has set out to create user personas in a bid to better understand the wide variety of audience who come to the website and subsequently move them through the subscription funnel.

“Their motivations and reasons for coming to the SCMP are very different, so we have to serve them in very different ways to grow them,” said Korey Lee, vice-president of data, SCMP.

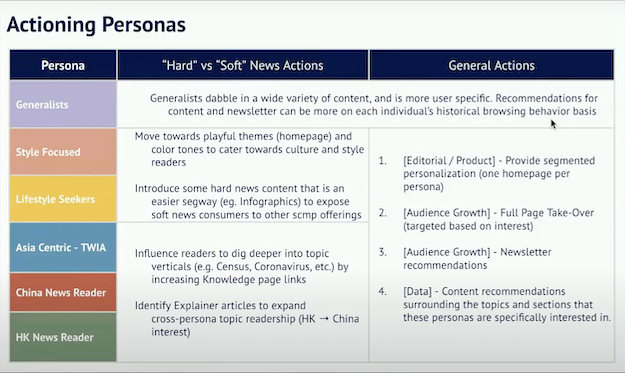

The problem is that a lot of data coming to the website is anonymous. So the publisher uses machine learning to cluster online behaviour and develop a set of actions based on these predictive personas. It wants to know if you are a ‘Chinese news reader’, a ‘style-focused reader’, or one of the many other categories it has carved out. SCMP solidified these profiles with real interviews and anecdotes.

In short: the user persona tool identifies what readers are doing, segments them into profiles and puts the most relevant product, editorial and marketing actions before them. For example, this means that how you ask a ‘Chinese news reader’ to subscribe differs from the process aimed at a ‘style-focused reader’.

Why? Because the data shows many different levels of engagement, propensity to subscribe and for what reason they come to the website.

Ideally, with any reader group, the publisher wants to broaden it, grow engagement, deepen loyalty, convert and retain its members. But some groups are just more limited than others, and this model shows how valuable they are. For example, just 0.01 per cent of style-focused readers are subscribed but they hang out on content that is usually paywalled.

“Understanding what each of these users is interested in, but also understanding where they are in the customer lifecycle or user journey, can help us expose them to the right actions in the funnel,” adds Lee.

When is the right time to offer a subscription? Do they need to be logged in first? Do they need to read more first? These are all important questions they are trying to answer.

SCMP plans to have different homepages for different personas in the future, which would allow to expose them to optimised content from the outset.